09 Sep Tsukiji Fish Market

Tsukiji fish market in Tokyo closed its doors for the last time this week prompting a revisit of photos taken there in October 2013.

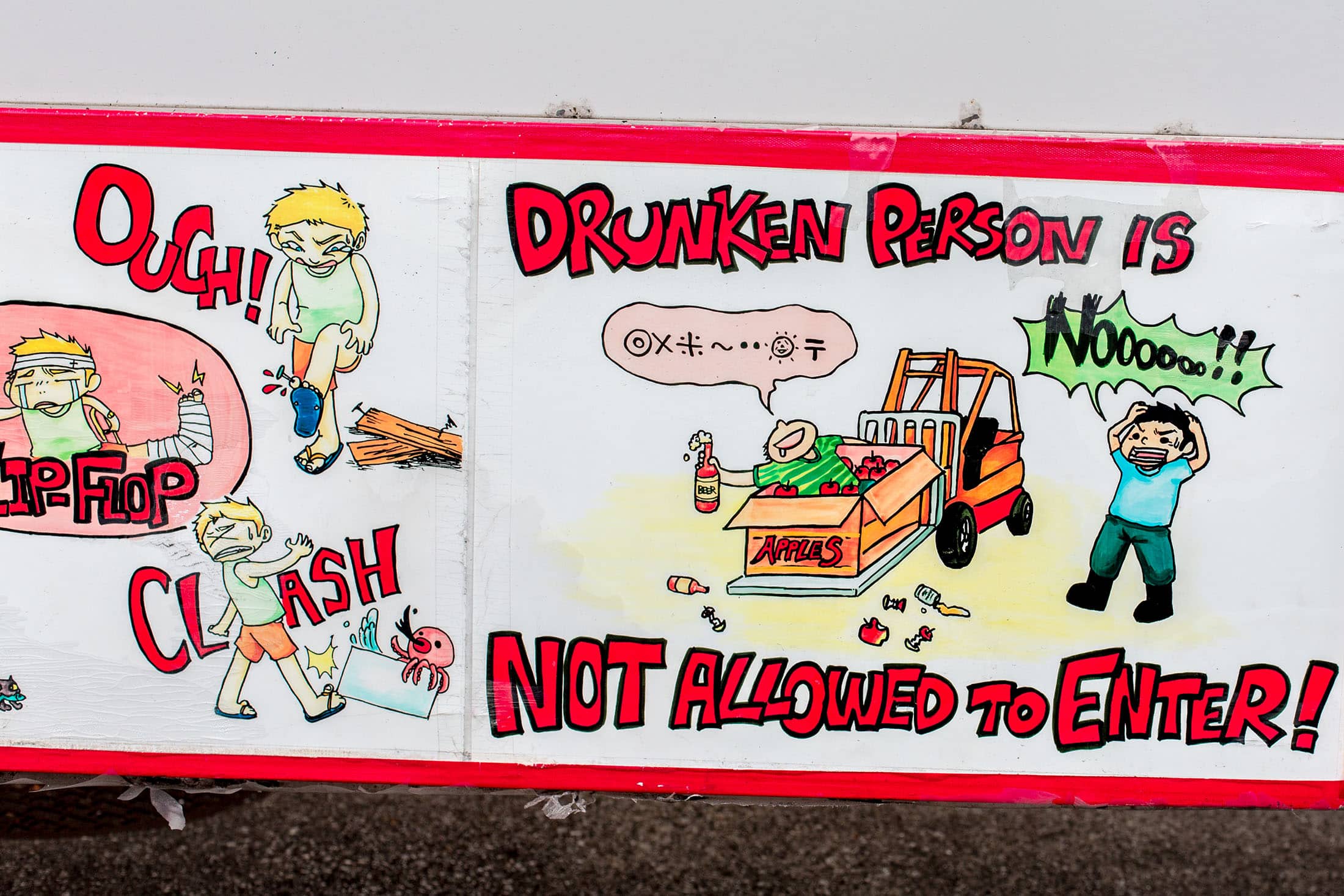

The first thing most people notice when they arrive at Tsukiji are the carts used to drive around the place – most notably because there are prominent signs telling visitors to keep out of the way of the workforce.

These carts are electric vehicles and very quiet moving around – another reason you need to keep your wits about you on site!

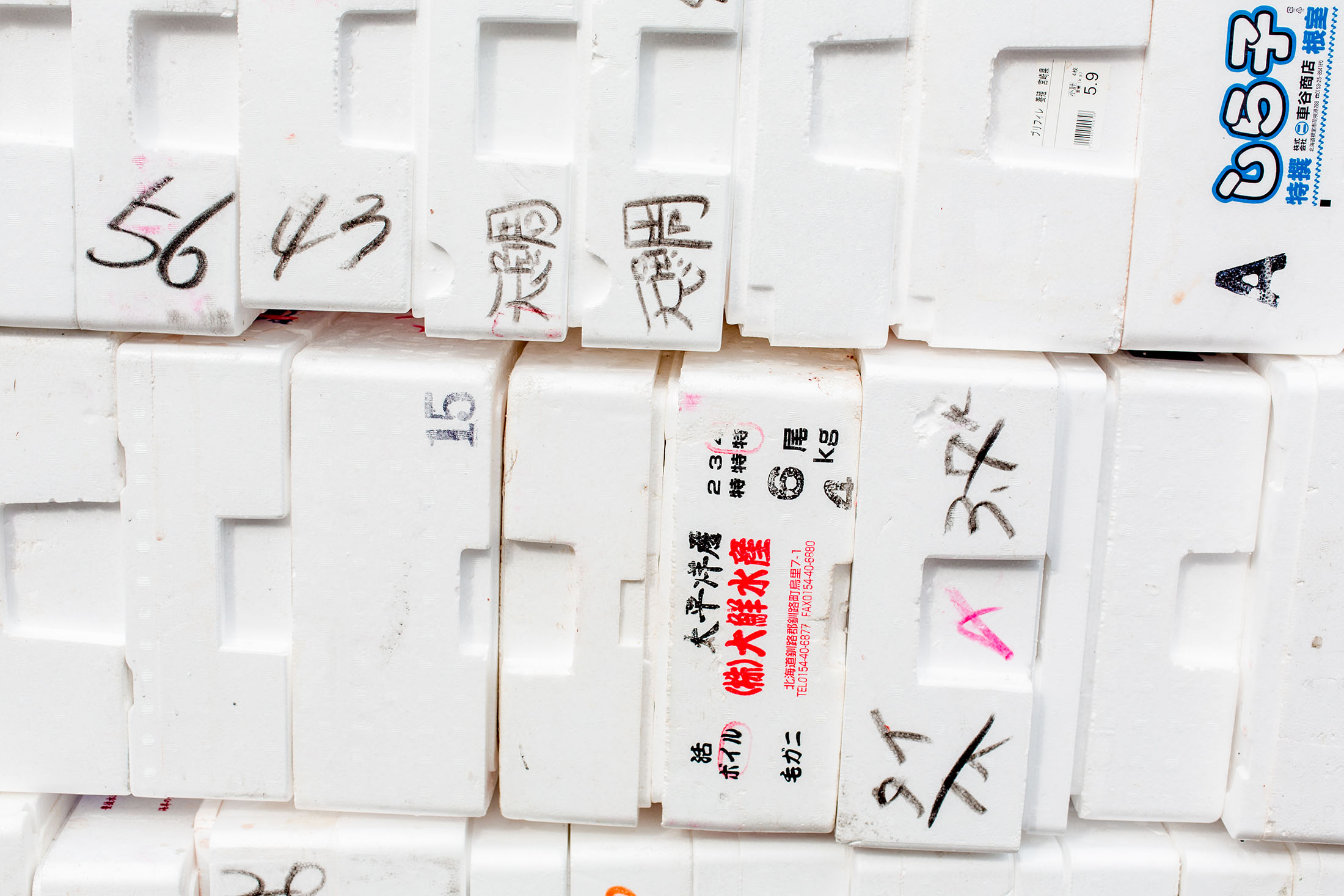

The next thing I always become aware of at the market is the inexhaustible variety of boxes; mostly polystyrene refrigeration boxes, but also crates, wooden pallets and and manner of string and packaging tape.

The Japanese have their own word to describe the art of wrapping things beautifully and appropriately – tsutsumu. Of course this fanaticism about packaging extends to the handling of fish. 1,700 tonnes of fish are processed at the market every day and whilst traditionally styrafoam is notoriously not biodegradable, according to their website, Tokyo Municipal government has found a way of recycling the styrofoam from Tsukiji.

One thing is for certain – the insatiable appetite for plastic at Tsukiji calls for a rigorous waste management plan and watching for just a few minutes easily reveals that such a plan is being executed daily at the site.

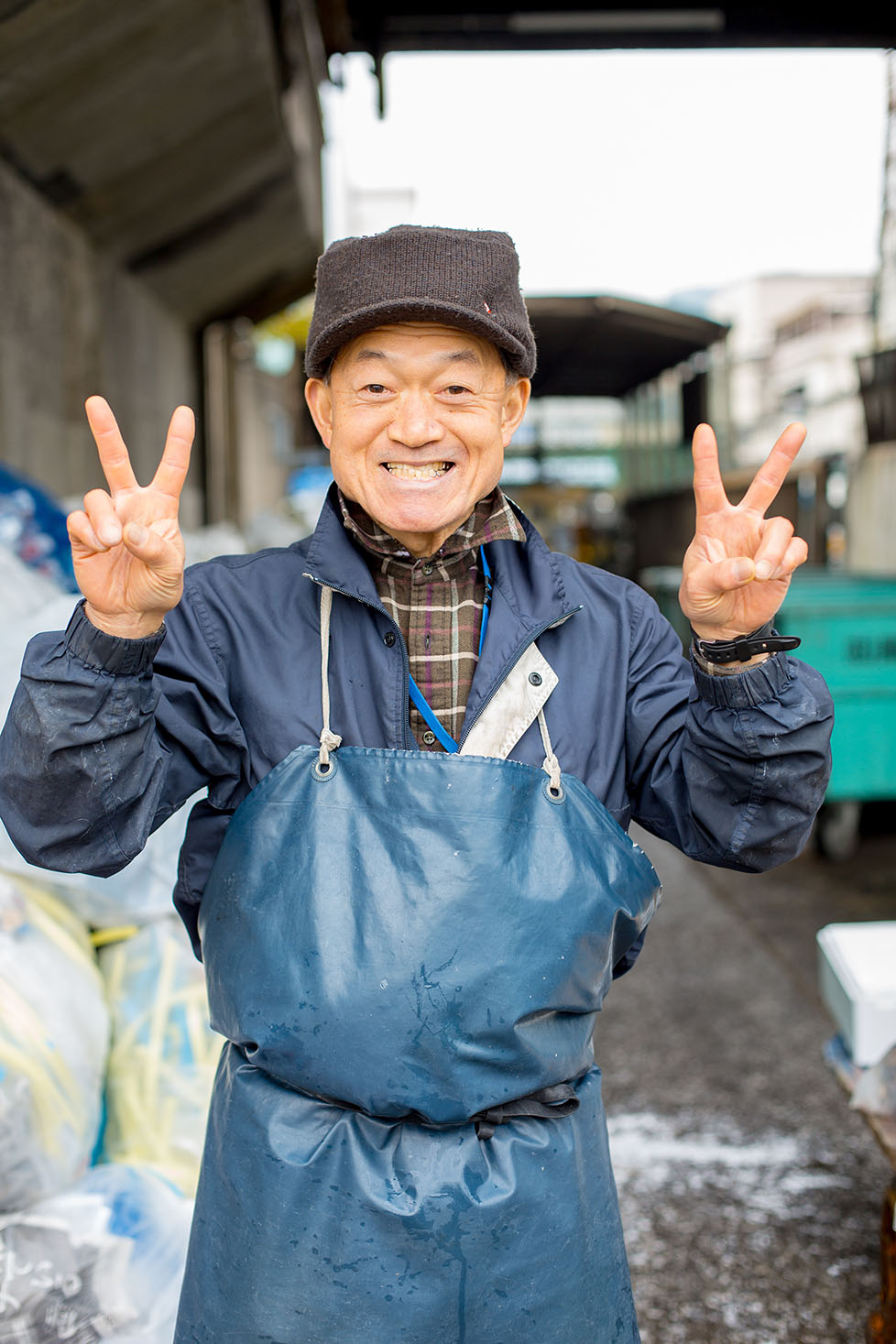

I have this guys number on a scrap of paper, it was 5 years ago and probably will be a few more before I return to Japan, but I hope to meet him again at the new Toyosu Market site in the future. His job is coordinating all the recycling and refuse leaving the inner market area.

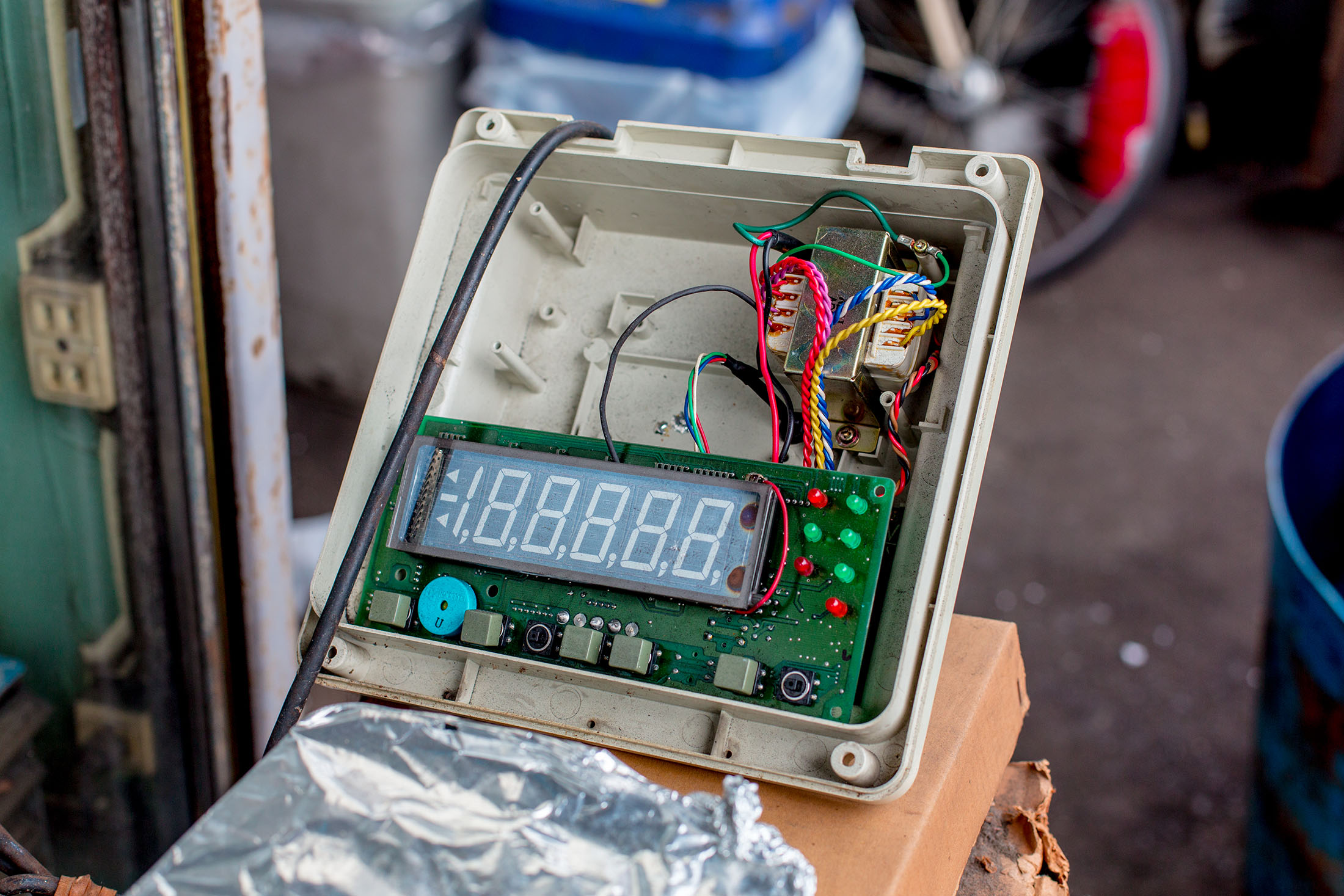

Another key player on the site is the master of scales. I photographed this ladies pile of old scales in 2010 and it was virtually unmoved when I returned in 2013 – I told her I had come back specifically to reshoot the pile of scales and she laughed and let me take her photo.

Other external characteristics of the market include the distinctive wooden carts, tool workshops and restaurants for the staff and visitors of all species.

One of the notable features of the new site at Toyosu is that the new market will operate in an enclosed block with advanced temperature control systems. These changes are overdue for businesses at Tsukiji and required to meet more stringent hygiene standards (and energy efficiency goals). It will also pave the way for traders to attain international trading certificates that some stalls have, until now, been unable to get.

After exploring the outside area I head into the main market at closing time. A cubists utopia but not for the squeamish, Tsukiji Market opens a myriad of sustainability questions but also possesses a sense of order and calm that allows visitors to find answer to such questions amongst its wooden beams and clean gullies.

As I left the market my attention was drawn to bigger stacks of boxes that were also on their way to leave Japan – and I hope to draw your attention to the much wider problems that the fishing industry faces internationally.

According to this firsthand account of a tuna auction, and fairly widely know facts about the industry:

On any given day, an Atlantic bluefin tuna caught off the coast of Maine will be bought by a local broker with links to Japanese auction houses using prices set by Tsukiji at the previous day’s auction. The fish is then stuffed into a long “tuna coffin” and trucked to John F Kennedy International Airport in New York City, where it will catch a flight to Tokyo’s Narita International Airport. When these fish arrive, they are immediately hauled away to the inspection area, placed next to catch from the rest of the world—Atlantic bluefin from Italy, Spain, Turkey; Pacific bluefin from California and Chile; southern ones from Australia and Indonesia—and also from Japanese ports such as Oma on the northern coast. The importer or auction company will take their bluefin, grade it and decide which of the 86 wholesale markets in Japan the tuna should go to. If it is deemed good enough for Tsukiji, it will be loaded on to trucks and sent to the auction house.

In some cases, a tuna might head back to Narita Airport for export to New York, London or Paris, where Michelin-starred chefs in sushi bars will serve it to diners for top dollar, pound and euro. In the global tuna trade, the most feared word is “domestic”. A “domestic” refers to a fish not good enough for Tsukiji. That means a fish that could have gone for $40-50 a pound will now be deemed worth a dollar or two at most. If your tuna is not good enough to make it to Tsukiji, you might as well not have killed it. - Abhijit Dutta

One thing is for certain: If the inside of the new global tuna industry is at Toyoshu, they will need to do more than impress the worlds ocean conservation organisations with arial views of green roofs and solar panels. The legacy of overfishing and waste in the piscatorial establishment must come to an end with the ascent of block chain technology, which is set to revolutionise supply chain transparency across all global markets in the next decade. The oceans deserve the same attention now as the carefully packaged fish at Tsukiji market has received for the last 100 years. Lets hope Japan can set a better example of sustainable fishing on the world stage from its new home.

No Comments